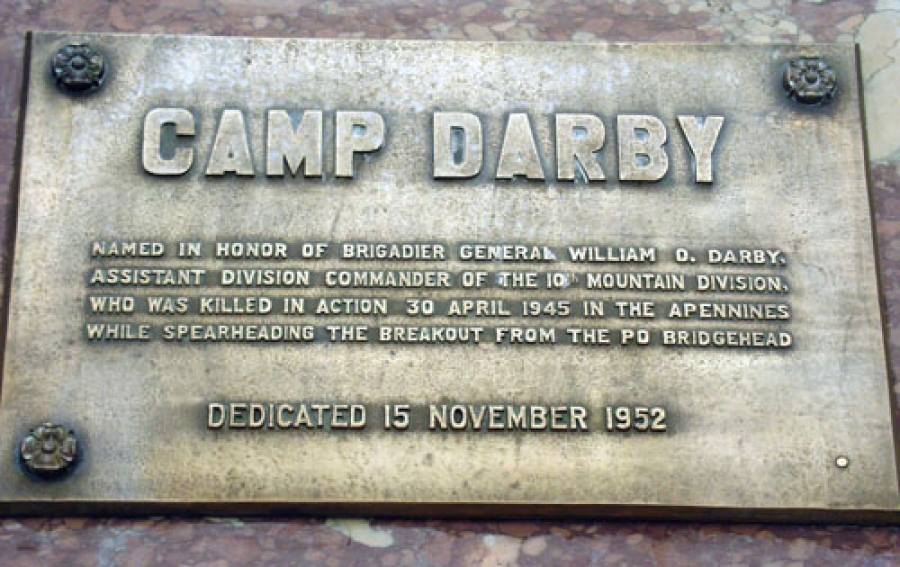

Camp Darby Namesake Plaque

Details:

In the center of the Post flag stand.

PlaqueA brass inscribed plaque mounted to a red stone pedestal about 4 feet off the ground.

Camp Darby is a US Army Installation located in Italy. The post is named after William O. Darby who fought with the Rangers and other units in Italy During World War 2. Camp Darby is still an operational base and has been since the end of World War 2.

Extract From the Defense Media Network about Darby and the Rangers:

“Col. William O. Darby - The Ranger Who Led the Way”

Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall ordered its existence. Gen. Lucian Truscott gave the unit its name. But the father of the Rangers was William Orlando Darby, its first commanding officer. A 1933 West Point graduate, he was a charismatic leader who would become one of the great troop commanders of World War II.

Darby organized, trained, and led the Rangers to triumphs in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. He also was there at Anzio, where his beloved Rangers suffered their greatest tragedy. After a period of stateside service, he would return to Italy, ultimately meeting a soldier’s death.

On June 8, 1942, Darby, now a major, received orders to form the 1st Ranger Battalion composed of “volunteers not averse to dangerous action.” More than 2,000 men stepped forward. Only about a third made the grade. The 1st Ranger Battalion was officially activated on June 19, 1942.

Training was based at Achnacarry Castle, Scotland, and conducted by British Commandos led by Lt. Col. Charles Vaughan, M.B.E.

During this period, 50 Rangers participated in Operation Jubilee, the raid on Dieppe, on Aug. 19, 1942, designed to test German army defenses on the French coast. When they returned, Darby said, “Their objective view of the Dieppe operation had its influence on future Ranger assaults.” The lessons Darby learned from listening to them was that the Rangers needed to do more: more training, more planning, more reconnaissance, and more intelligence.

In October 1942, Darby, now a lieutenant colonel, and his men boarded ship as one of the lead units in Operation Torch, the Anglo-American invasion of French North Africa.

Darby’s Rangers, as the unit was called, were ordered to capture two coastal defense batteries that dominated the landing beaches at Arzew, a port town near Oran – Fort de la Point, located at the water’s edge, and Batterie du Nord, located well inland and on a hill.

Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Torch’s overall commander, was so impressed by the Rangers’ action that he attempted to promote Darby to brigadier general. Darby declined, protesting that he was “not ready for it.” Darby knew that promotion would mean transfer to a new command, and he could not bear to leave his beloved Rangers.

After Arzew and a successful raid against Italian positions at Sened Station, where the Rangers earned the nickname “Black Devils,” many Rangers felt themselves blooded and experienced veterans. Darby knew much still needed to be done. He created a new training program that incorporated recent lessons learned in combat. It was “designed to make the experience in Scotland seem easy in comparison.”

At El Guettar, Tunisia, in March 1943, Darby faced a new challenge. Maj. Gen. Terry Allen, commander of the 1st Division, the “Big Red One,” needed to break through Italian army defenses in the rugged hills east of El Guettar. If the 1st Division made a frontal assault down the gravel track named Gumtree Road, it would end in disaster. Allen asked Darby if the Rangers could secretly bypass the Italian defenses and launch a surprise attack from the rear. Ranger patrols had discovered a path in a lightly held section on the northern flank. By following a circuitous, 12-mile route through the gorges of the area, Darby believed he could get his two battalions into attack position just five miles away “as the crow flies.” After taping their dogtags and blackening their faces, on the evening of March 20, Darby led 500 Rangers and 70 mortarmen into the night.

Then came the German counterattacks. Often outnumbered, the Rangers repelled one attack after another until they were relieved on March 27. Darby was proud of his men. Allen issued a letter of commendation that resulted in a Presidential Unit Citation.

While 1st Ranger Battalion went to bivouac, Darby went to Allied Headquarters at Algiers to discuss the Rangers’ role in Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. At that meeting, Darby was ordered to create and train in six weeks two additional Ranger battalions.

In recruiting for the 1st Rangers, Darby said, “There were sufficient cases of misfits to cause me to doubt the advisability of depending on volunteers.” Now he decided he would actively search for and select men he wanted. He believed the best men didn’t always volunteer. Darby found his men and within the allotted timeframe, the 1st, 3rd, and 4th Ranger Battalions were ready.

For Husky, Darby would lead Force X, composed of the 1st and 4th Rangers and support units, against the port of Gela. First Ranger Battalion would attack the defending fort and 4th Battalion would take out other coastal defenses in a predawn assault on July 10, 1943, before proceeding into the town. Dammer would lead the 3rd Rangers in the attack on Licata on the left flank.

Husky was followed by Operation Avalanche, the invasion of Italy at Salerno. The Rangers’ assignment was the seizure of the Sorrento Peninsula west of the city. Darby, commanding both Rangers and a British Commando force, surprised German troops north of the landing site and secured the high ground anchoring the Allied left flank. They had a clear view of the valley where German attacks would originate. This was crucial, for German response was furious. Darby later said, “If it hadn’t been for our standard operating procedure of carrying extra mortar shells ashore in the assault boats, we might well have lost our hold on Sorrento Peninsula.” Despite seven German counterattacks, Lt. Gen. Mark Clark, commander of the Fifth Army and later 15th Army Group, noted, “Darby’s fine leadership and the determination of his men turned back all assaults.”

Shingle was launched on Jan. 22, 1944. Initially, everything went well for Maj. Gen. John Lucas’ VI Corps. The landing was unopposed. Lucas immediately built up the shallow beachhead and cleared the port. But by the time Lucas turned his attention to the Alban hills, which dominated the landing site, the enemy had created a fearsome defense.

Lucas planned for a two-prong thrust on Jan. 30. The main attack would be on the left flank at Campoleone. Darby’s Rangers would participate in a secondary attack on the right at Cisterna. The 1st and 3rd Ranger Battalions would infiltrate what were believed to be thinly-held German lines and capture and hold the town until the 4th Ranger Battalion and other units arrived.

At 0100 on Jan. 30, with Darby controlling the action from a farmhouse headquarters, the Rangers began slipping through enemy lines. Too late, they discovered that the enemy was there in overwhelming force. The two battalions were trapped. Closest was the 4th Battalion, and it was stopped cold at Isola Bella, approximately two miles away. There was nothing Darby or Maj. Gen. Truscott, overall commander of the attack, could do.

Darby’s last recorded contact with the 1st Battalion before its surrender reflected his anguish and helplessness, “Issue some orders but don’t let the boys give up! … We’re coming through. Hang onto this radio until the last minute … stick together … use your head and do what’s best. … You’re there and I’m here, unfortunately, and I can’t help you, but whatever happens, God bless you!”

The Army’s official history recorded that “Of the 767 Rangers who had started toward Cisterna, only 6 returned; the rest were either dead or captured.” The surviving 4th Ranger Battalion suffered 50 percent casualties. Darby, devastated, blamed himself. The survivors were soon disbanded. Darby’s Rangers were no more.

On Feb. 16, the Germans launched a counteroffensive to destroy the Anzio beachhead. For five furious days, 10 German divisions smashed against five Allied divisions, driving them back to their final beachhead defensive line. One of the most beleaguered units was the U.S. 179th Infantry Regiment, which had suffered horrendous losses. By noon on Feb. 17, it was in danger of dissolving. Lucas ordered Darby to replace the exhausted commander and somehow restore order. Shortly after Darby arrived, the commander of the regiment’s 3rd Battalion appeared at Darby’s headquarters and said, “Sir, I guess you will relieve me for losing my battalion.” Darby patted the man on the back and said, “Cheer up, son. I just lost three of them, but the war must go on.” This comment, other words of encouragement, and vigorous action on Darby’s part restored the morale and confidence of the 179th. A shift of the German attack allowed Darby to stabilize his line. After a final, convulsive effort on Feb. 20, the German counteroffensive ended, a failure.

About two months later, Darby was assigned to the Operations Division of the War Department General Staff in Washington, D.C. He wrote reports, toured camps, and advised on training. Hating staff work, Darby constantly petitioned to return overseas. On March 29, 1945, he was assigned to evaluate aerial support of ground combat in Europe. While visiting the 10th Mountain Division in Italy, its assistant division commander was wounded and evacuated. Darby replaced him. Two days before the German surrender in Italy, Darby was fatally wounded by an 88 mm artillery round. He died at age 34.

The Rangers honor him with the William O. Darby Award, given to a graduating Ranger class member who “is the top Distinguished Honor Graduate” and who “clearly demonstrated himself as being a cut above all other Rangers.” The award is notable because each Ranger class is not required to have a recipient.

Monument Text:

The text is written in English and reads:

CAMP DARBY

NAMED IN HONOR OF BRIGADIER GENERAL WILLIAM O. DARBY,

ASSISTANT DIVISION COMMANDER OF THE 10TH MOUNTAIN DIVISION,

WHO WAS KILLED IN ACTION 30 APRIL 1945 IN THE APENNINES

WHILE SPEARHEADING THE BREAKOUT FORM THE PO BRIDGEHEAD

DEDICATED 15 NOVEMBER 1952

Commemorates:

People:

Units:

10th Mountain Division

179th Infantry Regiment, 45th Division

45th Infantry Division

5th Army

6615 Ranger Force

Darby's Rangers

Rangers

Wars:

Cold War

WWII

Other images :