Born on October 26, 1895 in Mississippi.During World War I, Joseph became a Cadet with the American Army, Aviation Section, Signal Corps. He was a membered of the Second Oxford Detachment for Aviation training in the UK. On the 7th of January 1918, whilst flying a DeHavilland 6 training aircraft over what is now RAF Waddington, Lincoln, England, Joseph was killed in an accident. Apparently the accident occurred on the last day of training.

Joseph was interred at the Newport Cemetery, Lincoln, England, War Graves Plot Section D, Grave 418. The grave is along side the graves of men of the Commonwealth who gave there lives in the two world wars. Joseph's is the only American grave in the cemetery.

The grave is cared for by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, as a Foreign National War Grave.

Source: Find a Grave

From the Men of the Second Oxford Detachment Website: Joseph Hiserodt Sharpe apparently attended school in Natchez and then in 1910 enrolled at Sewanee Military Academy in Tennessee.11 In the fall of 1913 he entered Mississippi Agricultural and Mechanical College, as Mississippi State University was then called, just east of Starkville (Eugene Hoy Barksdale enrolled a year after him there).12 Sharpe completed his studies in three years, graduating in 1916.13 He then relocated to Rock Island, Illinois, where his father had a number of relatives. These included Charles Extine Sharpe, who was associated with the Rock Island Plow Company; Joseph Hiserodt Sharpe was employed for a time in that company’s tractor department.14 When the U.S. entered the war, Sharpe enlisted. In May of 1917, he was accepted at the reserve officers training camp at Fort Sheridan in Illinois, where Walter Andrew Stahl and Vincent Paul Oatis, among many others, also trained.15 Sharpe, along with Stahl and Oatis, applied for and was accepted by the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and enrolled in the School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Illinois; their class graduated September 1, 1917.16

There was much speculation about where graduates from this ground school class would go for actual flying training, with information and plans changing frequently. The initial understanding, according to Oatis, was that the men would “go to Rantoul [Illinois] to the aviation field and pursue the actual flying game from three to four months.”17 However, in mid-August 1917, again according to Oatis, there was a request for volunteers “who would like to go to Italy for their air training. Right now Italy is about the best in the world in flying, so I grabbed at it and applied. Nearly everyone in our squadron did likewise.”18 After some further confusion as to whether some of those who had signed up might go to France instead, all but five of the thirty in this Illinois S.M.A. class became part of the detachment that set out from New York on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania, bound for Europe on the understanding that they, the 150 cadets of the “Italian detachment,” would learn to fly in Italy.19

The Carmania docked initially at Halifax, where she joined a convoy for the Atlantic crossing, which commenced on September 21, 1917. The men were assigned to first class; they enjoyed ship board leisure activities, including concerts featuring the violinist Albert Spalding. They also had Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, and, once they entered dangerous waters, they took turns at submarine watch.

Oxford and Grantham

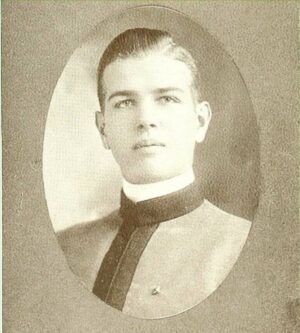

“Joe Sharpe,” from Milnor’s photo album. Perhaps taken during a bicycle ride near Oxford. (The photo is also preserved in Deetjen’s photo album.)

After an uneventful crossing, the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. There the cadets were ordered to proceed not to Italy as they expected, but to Oxford, where they were to attend ground school (again) under the auspices of the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics, much to their initial disgruntlement. Various explanations have been offered for the change of plans.20 Whatever the reason, the men of the detachment made their peace with the change and in retrospect recognized the benefits of R.F.C. training. Their British instructors, unlike those in the U.S., had had war flying experience, and this added considerable interest to the course work. Since the men had already covered much of the material, they did not have to study especially hard, and they enjoyed Oxford hospitality and explored the town and surrounding countryside. Another American detachment having already started ground school at Oxford in September, the one that arrived in October came to be called the “second Oxford detachment.”

Sharpe, perhaps at Grantham. From p. 67 of Mississippi Agricultural and Mechanical College, Bureau of War Records, The Mississippi Agricultural and Mechanical College War Record.

The men were eager to start learning to fly, but disappointment was in store for most of them at the end of four weeks at Oxford. The R.F.C. was able to accommodate twenty men from the detachment at No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford in early November, but the others, including Sharpe, set out on November 3, 1917, for Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend a machine gun course at Harrowby Camp. As Parr Hooper, also sent to Grantham, remarked: “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”21

At Grantham they spent two weeks learning about and practicing with the Vickers machine gun. Then, in mid-November, it was determined that there was room at training squadrons for fifty men, and Sharpe was among those selected. Along with nine others (Adolf M. Drey, William Wyman Mathews, George Orrin Middleditch, Oatis, Chester Albert Pudrith, Ervin David Shaw, Fred Trufant Shoemaker, Stahl, and Lynn Lemuel Stratton—all of whom, except Stratton and Shaw, had been in Sharpe’s ground school class in Illinois), he set off on November 19, 1917, for Waddington (about twenty miles north of Grantham and just south of Lincoln) where several R.F.C. training squadrons were located.22

Waddington

There is little direct documentation of Sharpe’s time at Waddington, but the log book and letters of Oatis are extant, and it is reasonable to assume that Sharpe’s training resembled that of Oatis. The latter did not do any flying during his first two weeks at Waddington—perhaps because he and his fellow cadets were being given yet more ground instruction, or perhaps because of poor weather or a lack of planes. In his first letter home from Waddington, dated December 11, 1917, Oatis is delighted finally to be flying: “It has taken a long long time to do it but we have finally killed the jinx. Last Tuesday we started flying and most of us are already soloing.” Oatis’s log book shows that late in the morning of Tuesday, December 4, 1917, he put in twenty-five minutes of dual flying in DH.6 (a two-seat plane designed for training). In his letter of December 11, 1917, he also reports that “Yesterday . . . Joe Sharpe took a plane up on a solo late in the afternoon and got lost. He didn’t show up at dark and we were all rather worried. He finally phoned in from Nottingham and reported that he had landed in a field when it got dark. Managed to get down safely.”

Over the course of December and early January, Oatis, and presumably also Sharpe, went up dual with instructors in R.E.8s and then also B.E.2e’s, both two-seater planes designed for reconnaissance and bombing, while also adding to their solo hours and practicing maneuvers in DH.6s.23

Oatis’s next letter, his first of the new year, brings the worst news: “Poor Joe Sharpe one of our old crowd from Champaign, was the first of our detachment to die. He was killed instantly in a bad crash on January 7. Nobody saw how the trouble started but it is believed he had tried to loop and lost control while upside down.”24 This initial uncertainty about the cause of the accident is reflected on the relevant casualty card, which describes the “Nature and Cause of Accident” as “Obscure,” but which also has added a transcription of the results of a court of inquiry: “Court found that the pilot was practicing looping or stalling, & beyond the vertical failed to right the machine which finally fell in an uncontrollable dive beyond the vertical.”25 The casualty card indicates Sharpe had been flying DH.6 A9761.

From “America Flyer Killed in France.”

According to Oatis, “[Sharpe’s] parents were notified officially, and we all cabled our condolences.”26 The condolences, sent to Natchez, appear to have arrived first: “We send sincere sympathy in the loss of our true friend and comrade, Joseph Sharpe. He leaves the memory of a noble life unselfishly given. Effects cared for. Letters follow. [signed] His American comrades / Walter Sohle [sic: sc. Stahl].”27 According to the Natchez Democrat of January 9, 1918, “The message was received by Mr. Brown, who, with his wife, went to the plantation home at Lamarque to break the sad news”—Frederick Davis Brown of Natchez was married to the former Josephine Hiserodt, sister of Sharpe’s mother. A confirming telegram sent by Adjutant General Henry Pinckney McCain is dated January 10, 1918: “Deeply regret to confirm report of death of J. H. Sharpe, aviation corps. Official telegram sent you at La Marque, La.”28 Arthur Shuldham Redfern, the C.O. of No. 48 Training Squadron at Waddington, wrote to Sharpe’s father the day of the accident; Mr. Sharpe received it in early February.28a

Unsurprisingly, news of Sharpe’s death spread quickly among members of the second Oxford detachment. Jesse Frank Campbell, at London Colney, wrote of it in his diary on January 8, 1918 (incorrectly identifying the plane as an R.E.8; this misidentification is repeated in the January 12, 1918, entry in War Birds). John McGavock Grider, also at London Colney, mentions Sharpe’s death in a letter written sometime in January 1918.29 William Ludwig Deetjen, at Stamford, wrote in his diary on January 11, 1918, that he “Just heard that Sharpe of our Italian Outfit had been killed by a vertical dive in a deH6,” and then on January 18, 1918, having himself just been posted to Waddington: “Joe Sharpe was a mighty fine lad and we all loved him. Too bad that the best men go first.”

“Joe’s coffin and hat,” from Milnor’s photo album.

Oatis recounts how Sharpe “was buried with military honors in Lincoln on January 11, six of us who have been together since we joined the aviation corps acting as pall bearers. His untimely and tragic end gave us an awful shock. It was hard to stand beside that grave in a little English churchyard and hear the salute fired, and a bugler blowing ‘taps’ over the body of our pal.”30 The six pall bearers were presumably, in addition to Oatis, five of the six other Illinois S.M.A. graduates at Waddington (Drey, Mathews, Middleditch, Pudrith, Shoemaker, and Stahl).

Middleditch and Pudrith were later buried in the same “U.S.A. plot” at Newport Cemetery in Lincoln, as were second Oxford detachment members Donald Elsworth Carlton and Elwood D. Stanbery. American next of kin of those killed in Europe in World War I were allowed to choose whether a body should remain there or be returned to the U.S. Carlton and Middleditch were eventually reinterred in Brookwood American Military Cemetery in Surrey; the bodies of Pudrith and Stanbery were returned to the U.S.

Sharpe’s father “was deeply torn on moving his son Joseph from his solitary grave. At first he wanted his son’s body sent home; he then changed his mind, requesting that the body remain in Europe and that he be allowed to supervise its exhumation . . . for reburial in a military cemetery there. . . .”31 This was not permitted, and ultimately Sharpe’s body remained where he was first interred, the only American in the cemetery.

PRIVATE CITIZENS SUPPORTING AMERICA'S HERITAGE

American

War Memorials Overseas, Inc.

War Memorials Overseas, Inc.

Sharpe Joseph Hiserodt

Name:

Joseph Hiserodt Sharpe

Rank:

Cadet

Serial Number:

Unit:

US Army Aviation Signal Corps

Date of Death:

1918-01-07

State:

Mississippi

Cemetery:

Newport Cemetery (CWGC) Lincoln, City of Lincoln, Lincolnshire, England

Plot:

Section D

Row:

Grave:

418

Decoration:

Comments: